Can a Baby Still Be Born if Mom Has Chlamydia

| Chlamydia trachomatis | |

|---|---|

| |

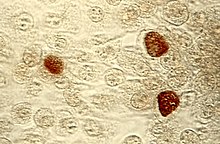

| Chlamydia trachomatis in chocolate-brown | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Leaner |

| Phylum: | Chlamydiota |

| Class: | Chlamydiia |

| Lodge: | Chlamydiales |

| Family: | Chlamydiaceae |

| Genus: | Chlamydia |

| Species: | C. trachomatis |

| Binomial name | |

| Chlamydia trachomatis (Busacca 1935) Rake 1957 emend. Everett et al. 1999[1] | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Chlamydia trachomatis (), ordinarily known as chlamydia,[two] is a bacterium that causes chlamydia, which can manifest in various ways, including: trachoma, lymphogranuloma venereum, nongonococcal urethritis, cervicitis, salpingitis, pelvic inflammatory affliction. C. trachomatis is the nearly common infectious cause of blindness and the most common sexually transmitted bacterium.[iii]

Different types of C. trachomatis cause unlike diseases. The most common strains cause illness in the genital tract, while other strains cause disease in the eye or lymph nodes. Like other Chlamydia species, the C. trachomatis life cycle consists of two morphologically distinct life stages: elementary bodies and reticulate bodies. Uncomplicated bodies are spore-like and infectious, whereas reticulate bodies are in the replicative stage and are seen only inside host cells.

Description [edit]

Chlamydia trachomatis is a gram-negative bacterium that can replicate only inside a host jail cell.[3] Over the course of the C. trachomatis life cycle, the leaner have on two distinct forms. Simple bodies are 200 to 400 nanometers across, and are surrounded by a rigid jail cell wall that allows them to survive outside of a host jail cell.[3] [4] This form can initiate a new infection if it comes into contact with a susceptible host cell.[3] Reticulate bodies are 600 to 1500 nanometers across, and are found only within host cells.[4] Neither class is motile.[iv]

The C. trachomatis genome is substantially smaller than that of many other bacteria at approximately one.04 megabases, encoding approximately 900 genes.[3] Several important metabolic functions are not encoded in the C. trachomatis genome, and instead, are likely scavenged from the host prison cell.[iii] In addition to the chromosome that contains most of the genome, almost all C. trachomatis strains carry a 7.five kilobase plasmid that contains 8 genes.[4] The office of this plasmid is unknown, though strains without the plasmid have been isolated, suggesting it is non required for survival of the bacterium.[4]

Life cycle [edit]

Like other Chlamydia species, C. trachomatis has a life cycle consisting of two morphologically singled-out forms. Starting time, C. trachomatis attaches to a new host cell as a small spore-like form called the elementary torso.[5] The elementary torso enters the host cell, surrounded by a host vacuole, chosen an inclusion.[5] Within the inclusion, C. trachomatis transforms into a larger, more than metabolically active course chosen the reticulate body.[5] The reticulate body substantially modifies the inclusion, making information technology a more hospitable environment for rapid replication of the bacteria, which occurs over the following 30 to 72 hours.[five] The massive number of intracellular bacteria and so transition back to resistant simple bodies, before causing the cell to rupture and being released into the surroundings.[5] These new elementary bodies are then shed in the semen or released from epithelial cells of the female genital tract, and attach to new host cells.[6]

Nomenclature [edit]

C. trachomatis are leaner in the genus Chlamydia, a group of obligate intracellular parasites of eukaryotic cells.[3] Chlamydial cells cannot carry out free energy metabolism and they lack biosynthetic pathways.[vii]

C. trachomatis strains are more often than not divided into three biovars based on the type of disease they cause. These are further subdivided into several serovars based on the surface antigens recognized by the immune system.[3] Serovars A through C cause trachoma, which is the world'southward leading cause of preventable infectious blindness.[8] Serovars D through M infect the genital tract, causing pelvic inflammatory affliction, ectopic pregnancies, and infertility. Serovars L1 through L3 cause an invasive infection of the lymph nodes near the genitals, called lymphogranuloma venereum.[3]

C. trachomatis is thought to have diverged from other Chlamydia species around half dozen million years agone. This genus contains a total of nine species: C. trachomatis, C. muridarum, C. pneumoniae, C. pecorum, C. suis, C. abortus, C. felis, C. caviae, and C. psittaci. The closest relative to C. trachomatis is C. muridarum, which infects mice.[5] C. trachomatis along with C. pneumoniae accept been found to infect humans to a greater extent. C. trachomatis exclusively infects humans. C. pneumoniae is establish to as well infect horses, marsupials, and frogs. Some of the other species tin have a considerable impact on man health due to their known zoonotic manual.[ citation needed ]

| Strains that cause lymphogranuloma venereum (Serovars L1 to L3) | |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

Role in affliction [edit]

Clinical signs and symptoms of C. trachomatis infection in the ballocks nowadays as the chlamydia infection, which may be asymptomatic or may resemble a gonorrhea infection.[9] Both are common causes of multiple other atmospheric condition including pelvic inflammatory illness and urethritis.[ten]

C. trachomatis is the single almost important infectious agent associated with blindness (trachoma), and it as well affects the eyes in the form of inclusion conjunctivitis and is responsible for about nineteen% of adult cases of conjunctivitis.[11]

C. trachomatis in the lungs presents as the chlamydia pneumoniae respiratory infection and can affect all ages.[ citation needed ]

Pathogenesis [edit]

Elementary bodies are generally present in the semen of infected men and vaginal secretions of infected women.[6] When they come into contact with a new host cell, the simple bodies bind to the jail cell via interaction between adhesins on their surface and several host receptor proteins and heparan sulfate proteoglycans.[3] Once attached, the bacteria inject various effector proteins into the host cell using a type three secretion arrangement.[3] These effectors trigger the host jail cell to take up the elementary bodies and prevent the cell from triggering apoptosis.[3] Within 6 to viii hours afterward infection, the elementary bodies transition to reticulate bodies and a number of new effectors are synthesized.[3] These effectors include a number of proteins that modify the inclusion membrane, called Inc proteins, too as proteins that redirect host vesicles to the inclusion.[3] 8 to 16 hours after infection, another set up of effectors are synthesized, driving acquisition of nutrients from the host cell.[3] At this stage, the reticulate bodies brainstorm to dissever, coinciding with the expansion of the inclusion.[3] If several elementary bodies take infected a single prison cell, their inclusions will fuse at this point to create a unmarried large inclusion in the host prison cell.[3] From 24 to 72 hours later infection, reticulate bodies transition to elementary bodies which are released either by lysis of the host cell or extrusion of the entire inclusion into the host genital tract.[iii]

Presentation [edit]

Most people infected with C. trachomatis are asymptomatic. However, the bacteria can present in one of 3 ways: genitourinary (genitals), pulmonary (lungs), and ocular (eyes).[12]

Genitourinary cases tin include genital discharge, vaginal bleeding, itchiness (pruritus), painful urination (dysuria), among other symptoms.[13] Oftentimes, symptoms are similar to those of a urinary tract infection.

When C. trachomatis presents in the heart in the form of trachoma it begins by gradually thickening the eyelids, and eventually begins to pull the eyelashes into the eyelid.[fourteen] In the form of inclusion conjunctivitis the infection presents with redness, swelling, mucopurulent discharge from the heart, and most other symptoms associated with adult conjunctivitis.[11]

When C. trachomatis is in the lungs in the form of a respiratory infection information technology typically has symptoms of a runny or stuffy nose, low-grade fever, hoarseness of phonation, as well as other symptoms associated with general pneumonia.[15]

C. trachomatis may latently infect the chorionic villi tissues of meaning women, thereby impacting pregnancy event.[xvi]

Prevalence [edit]

Three times every bit many women are diagnosed with genitourinary C. trachomatis infections than men. Women aged 15–19 have the highest prevalence, followed by women anile 20–24, although the rate of increase of diagnosis is greater for men than for women. Risk factors for genitourinary infections include unprotected sex activity with multiple partners, lack of prophylactic use, and depression socioeconomic status living in urban areas.[12]

Pulmonary infections tin occur in infants born to women with agile chlamydia infections, although the rate of infection is less than ten%.[13]

Ocular infections take the course of inclusion conjunctivitis or trachoma, both in adults and children. Virtually 84 million worldwide suffer C. trachomatis centre infections and 8 one thousand thousand are blinded every bit a consequence of the infection.[17] Trachoma is the primary source of infectious blindness in some parts of rural Africa and Asia[18] and is a neglected tropical disease that has been targeted by the World Health Organization for emptying past 2020. Inclusion conjunctivitis from C. trachomatis is responsible for about 19% of adult cases of conjunctivitis.[xi]

Treatment [edit]

Handling depends on the infection site, age of the patient, and whether some other infection is nowadays. Having a C. trachomatis and ane or more other sexually transmitted infections at the same time is possible. Handling is often done with both partners simultaneously to forestall reinfection. C. trachomatis may exist treated with several antibiotic medications, including azithromycin, erythromycin, ofloxacin,[ix] and tetracycline.

Tetracycline is the most preferred antibiotic to treat C.trachomatis and has the highest success rate. Azithromycin and doxycycline have equal efficacy to treat C. trachomatis with 97 and 98 percent success, respectively. Azithromycin is dosed as a 1 gram tablet that is taken by mouth every bit a single dose, primarily to assistance with concerns of non-adherence.[19] Handling with generic doxycycline 100 mg twice a day for 7 days has equal success with expensive delayed-release doxycycline 200 mg once a day for 7 days.[xix] Erythromycin is less preferred equally it may cause gastrointestinal side effects, which can atomic number 82 to non-adherence. Levofloxacin and ofloxacin are mostly no better than azithromycin or doxycycline and are more than expensive.[19]

If treatment is necessary during pregnancy, levofloxacin, ofloxacin, tetracycline, and doxycycline are non prescribed. In the case of a patient who is pregnant, the medications typically prescribed are azithromycin, amoxicillin, and erythromycin. Azithromycin is the recommended medication and is taken as a 1 gram tablet taken by oral fissure as a single dose.[19] Despite amoxicillin having fewer side effects than the other medications for treating antenatal C. trachomatis infection, there have been concerns that pregnant women who take penicillin-grade antibiotics tin develop a chronic persistent chlamydia infection.[xx] Tetracycline is non used because some children and even adults can not withstand the drug, causing harm to the mother and fetus.[19] Retesting during pregnancy can exist performed 3 weeks after treatment. If the gamble of reinfection is high, screening can be repeated throughout pregnancy.[nine]

If the infection has progressed, ascending the reproductive tract and pelvic inflammatory illness develops, impairment to the fallopian tubes may have already occurred. In almost cases, the C. trachomatis infection is then treated on an outpatient basis with azithromycin or doxycycline. Treating the female parent of an infant with C. trachomatis of the eye, which can evolve into pneumonia, is recommended.[ix] The recommended handling consists of oral erythromycin base or ethylsuccinate 50 mg/kg/twenty-four hour period divided into 4 doses daily for 2 weeks while monitoring for symptoms of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis (IHPS) in infants less than half dozen weeks sometime.[nineteen]

There have been a few reported cases of C.trachomatis strains that were resistant to multiple antibiotic treatments. However, as of 2018, this is not a major cause of concern as antibiotic resistance is rare in C.trachomatis compared to other infectious bacteria.[21]

Laboratory tests [edit]

Chlamydia species are readily identified and distinguished from other Chlamydia species using Deoxyribonucleic acid-based tests. Tests for Chlamydia tin can be ordered from a doc, a lab or online.[22]

Most strains of C. trachomatis are recognized by monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) to epitopes in the VS4 region of MOMP.[23] All the same, these mAbs may too cross-react with two other Chlamydia species, C. suis and C. muridarum.

- Nucleic acrid distension tests (NAATs) tests detect the genetic cloth (DNA) of Chlamydia bacteria. These tests are the nigh sensitive tests available, meaning they are very accurate and are very unlikely to accept false-negative test results. A polymerase chain reaction (PCR) exam is an instance of a nucleic acid distension exam. This examination can too exist done on a urine sample, urethral swabs in men, or cervical or vaginal swabs in women.[24]

- Nucleic acrid hybridization tests (DNA probe test) also discover Chlamydia Deoxyribonucleic acid. A probe test is very accurate merely is not as sensitive equally NAATs.

- Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA, EIA) finds substances (Chlamydia antigens) that trigger the immune organization to fight Chlamydia infection. Chlamydia Elementary body (EB)-ELISA could exist used to stratify different stages of infection based upon Immunoglobulin-γ status of the infected individuals [25]

- Direct fluorescent antibody test also finds Chlamydia antigens.

- Chlamydia cell culture is a examination in which the suspected Chlamydia sample is grown in a vial of cells. The pathogen infects the cells, and after a ready incubation fourth dimension (48 hours), the vials are stained and viewed on a fluorescent calorie-free microscope. Cell culture is more than expensive and takes longer (two days) than the other tests. The civilization must exist grown in a laboratory.[26]

Research [edit]

Due to its significance to human wellness, C. trachomatis is the subject of inquiry in laboratories around the earth. The leaner are usually grown in immortalised jail cell lines such every bit McCoy cells (see RPMI 1640) and HeLa cells.[4] Infectious particles can be quantified by infecting cell layers and counting the number of inclusions, analogous to a plaque assay.[4] Recent research has found that a pair of disulfide bail proteins, which are necessary for C. trachomatis to be able to infect host cells, is very like to a homologous pair of proteins found in Escherichia coli (Eastward. coli), though the reaction'south speed is slower in C. trachomatis.[ citation needed ]

Other research has been conducted to endeavor to go a experience for how to create a vaccine against C. trachomatis, finding that it would be very difficult to create a fully effective or even partially effective vaccine since the host's response to infection involves complex immunological pathways that must first exist fully understood to ensure that agin furnishings are avoided.[27]

Vaccine [edit]

In August 2016 a Phase I phase i, double-bullheaded, parallel, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial was undertaken by the Danish Statens Serum Institut at Hammersmith Hospital in London, Britain, in salubrious women aged nineteen–45 years. The trial aimed to appraise the safety and ability to provoke an allowed response of the CTH522 chlamydia vaccine. 35 women not infected with chlamydia were included in the trial. The trial included ii adjuvants and a saline control group. The vaccine was found to be safety, and all women who received the vaccine regardless of adjuvant developed an immune response against chlamydia.[28]

The Serum Found has announced that it will continue to pursue funding to move the vaccine into a Phase Two trial.[29]

History [edit]

C. trachomatis was first described in 1907 past Stanislaus von Prowazek and Ludwig Halberstädter in scrapings from trachoma cases.[30] [v] Thinking they had discovered a "mantled protozoan", they named the organism "Chlamydozoa" from the Greek "Chlamys" meaning mantle.[5] Over the next several decades, "Chlamydozoa" was idea to be a virus equally it was small enough to pass through bacterial filters and unable to grow on known laboratory media.[v] However, in 1966 electron microscopy studies showed C. trachomatis to exist a bacterium.[five] This is substantially due to the fact that they were institute to possess DNA, RNA, and ribosomes similar other bacteria. It was originally believed that Chlamydia lacked peptidoglycan considering researchers were unable to notice muramic acid in jail cell extracts.[31] Subsequent studies determined that C. trachomatis synthesizes both muramic acid and peptidoglycan, merely relegates it to the microbe'south division septum and does not use information technology for construction of a cell wall.[32] [33] The bacterium is nevertheless classified as gram-negative[34]

C. trachomatis agent was first cultured and isolated in the yolk sacs of eggs past Tang Fei-fan et al. in 1957.[35] This was a significant milestone because it became possible to preserve these agents which could then be used for future genomic and phylogenetic studies. The isolation of C. trachomatis coined the term isolate to describe how C. trachomatis has been isolated from an in vivo setting into a "strain" in cell culture.[36] But a few "isolates" have been studied in item, limiting the data that can be constitute on the evolutionary history of C. trachomatis.[35] [37]

Development [edit]

In the 1990s it was shown that there are several species of Chlamydia. Chlamydia trachomatis was first described in historical records in Ebers papyrus written between 1553 and 1550 BC.[38] In the aboriginal world, it was known as the blinding affliction trachoma. The disease may have been closely linked with humans and likely predated civilization.[39] Information technology is now known that C. trachomatis comprises 19 serovars which are identified past monoclonal antibodies that react to epitopes on the major outer-membrane protein (MOMP).[forty] Comparing of amino acid sequences reveals that MOMP contains four variable segments: S1,2 ,iii and 4. Different variants of the factor that encodes for MOMP, differentiate the genotypes of the different serovars. The antigenic relatedness of the serovars reflects the homology levels of Dna between MOMP genes, especially inside these segments.[41]

Furthermore, at that place have been over 220 Chlamydia vaccine trials done on mice and other non-human host species to target C. muridarum and C. trachomatis strains. All the same, it has been difficult to translate these results to the human species due to physiological and anatomical differences. Future trials are working with closely related species to the human.[42]

See as well [edit]

- Translocated actin-recruiting phosphoprotein

References [edit]

- ^ J.P. Euzéby. "Chlamydia". List of Prokaryotic names with Standing in Nomenclature . Retrieved 2008-09-eleven .

- ^ "Chlamydia trachomatis". Retrieved 2015-11-18 . [ expressionless link ]

- ^ a b c d eastward f yard h i j k l m n o p q r Elwell C, Mirrashidi K, Engel J (2016). "Chlamydia cell biology and pathogenesis". Nature Reviews Microbiology. fourteen (6): 385–400. doi:10.1038/nrmicro.2016.30. PMC4886739. PMID 27108705.

- ^ a b c d east f m Kuo CC, Stephens RS, Bavoil PM, Kaltenboeck B (2015). "Chlamydia". In Whitman WB (ed.). Bergey's Manual of Systematics of Archaea and Bacteria. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 1–28. doi:10.1002/9781118960608.gbm00364. ISBN9781118960608.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Nunes A, Gomes JP (2014). "Evolution, Phylogeny, and molecular epidemiology of Chlamydia". Infection, Genetics and Evolution. 23: 49–64. doi:10.1016/j.meegid.2014.01.029. PMID 24509351.

- ^ a b Witkin SS, Minis East, Athanasiou A, Leizer J, Linhares IM (2017). "Chlamydia trachomatis:the persistent pathogen". Clinical and Vaccine Immunology. 24 (x): e00203–17. doi:x.1128/CVI.00203-17. PMC5629669. PMID 28835360.

- ^ Becker, Y. (1996). Molecular evolution of viruses: Past and present (4th ed.). Dordrecht: Kluwer Bookish. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK8091/.

- ^ Burton, Matthew J.; Trachoma: an overview, British Medical Bulletin, Volume 84, Issue 1, 1 Dec 2007, Pages 99–116, https://doi.org/10.1093/bmb/ldm034

- ^ a b c d Malhotra Chiliad, Sood S, Mukherjee A, Muralidhar Southward, Bala M (September 2013). "Genital Chlamydia trachomatis: an update". Indian J. Med. Res. 138 (3): 303–16. PMC3818592. PMID 24135174.

- ^ Fredlund H, Falk L, Jurstrand M, Unemo M (2004). "Molecular genetic methods for diagnosis and characterisation of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae: touch on epidemiological surveillance and interventions". APMIS. 112 (11–12): 771–84. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0463.2004.apm11211-1205.10. PMID 15638837. S2CID 25249521.

- ^ a b c Rapoza, Peter A.; Quinn, Thomas C.; Terry, Arlo C.; Gottsch, John D.; Kiessling, Lou Ann; Taylor, Hugh R. (1990-02-01). "A Systematic Arroyo to the Diagnosis and Treatment of Chronic Conjunctivitis". American Periodical of Ophthalmology. 109 (2): 138–142. doi:10.1016/S0002-9394(14)75977-X. ISSN 0002-9394. PMID 2154106.

- ^ a b "Chlamydial Infections". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library . Retrieved 8 July 2021.

- ^ a b Mishori R, McClaskey EL, WinklerPrins VJ (fifteen Dec 2012). "Chlamydia Trachomatis Infections: Screening, Diagnosis, and Direction". American Family Physician. 86 (12): 1127–1132. PMID 23316985.

- ^ Wolle, Meraf A.; Due west, Sheila K. (2019-03-04). "Ocular Chlamydia trachomatis infection: elimination with mass drug assistants". Expert Review of Anti-infective Therapy. 17 (3): 189–200. doi:10.1080/14787210.2019.1577136. ISSN 1478-7210. PMC7155971. PMID 30698042.

- ^ "Recommendations for the Prevention and Management of Chlamydia trachomatis Infections, 1993". world wide web.cdc.gov . Retrieved 2019-11-05 .

- ^ Contini C, Rotondo JC, Magagnoli F, Maritati Grand, Seraceni Due south, Graziano A, Poggi A, Capucci R, Vesce F, Tognon Grand, Martini F (2018). "Investigation on silent bacterial infections in specimens from pregnant women affected by spontaneous miscarriage". J Cell Physiol. 234 (1): 100–9107. doi:10.1002/jcp.26952. PMID 30078192.

- ^ "Trachoma". Prevention of Incomprehension and Visual Impairment. World Health Organization. Archived from the original on January 28, 2011.

- ^ Global Network for Neglected Tropical Diseases. Trachoma interactive fact canvas.http://sometime.globalnetwork.org/sites/all/modules/ globalnetwork/factsheetxml/affliction.php?id=9. Accessed Feb vi, 2011,

- ^ a b c d e f "Chlamydial Infections in Adolescents and Adults". Retrieved January 23, 2017.

- ^ Welsh, 50 E; Gaydos, C A; Quinn, T C (1992). "In vitro evaluation of activities of azithromycin, erythromycin, and tetracycline against Chlamydia trachomatis and Chlamydia pneumoniae". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 36 (two): 291–294. doi:10.1128/aac.36.two.291. ISSN 0066-4804. PMC188358. PMID 1318677.

- ^ Mestrovic, T (2018). "Molecular Mechanisms of Chlamydia trachomatis resistance to antimicrobial drugs" (PDF). Frontiers in Bioscience. 23 (2): 656–670. doi:10.2741/4611. PMID 28930567. S2CID 11631854.

- ^ "Oral Chlamydia Dwelling house Testing, Symptoms and Treatment | myLAB Box™". 2019-04-03.

- ^ Ortiz Fifty, Angevine G, Kim SK, Watkins D, DeMars R (2000). "T-Cell Epitopes in Variable Segments of Chlamydia trachomatis Major Outer Membrane Protein Elicit Serovar-Specific Immune Responses in Infected Humans". Infect. Immun. 68 (3): 1719–23. doi:10.1128/IAI.68.iii.1719-1723.2000. PMC97337. PMID 10678996.

- ^ Toll, Malcolm J; Ades, AE; Soldan, Kate; Welton, Nicky J; Macleod, John; Simms, Ian; DeAngelis, Daniela; Turner, Katherine ME; Horner, Paddy J (2016). "The natural history of Chlamydia trachomatis infection in women: a multi-parameter evidence synthesis". Health Technology Assessment. 20 (22): 1–250. doi:ten.3310/hta20220. ISSN 1366-5278. PMC4819202. PMID 27007215.

- ^ Bakshi, Rakesh; Gupta, Kanupriya; Jordan, Stephen J.; Brown, LaDraka' T.; Press, Christen Thou.; Gorwitz, Rachel J.; Papp, John R.; Morrison, Sandra G.; Lee, Jeannette Y. (2017-04-21). "Immunoglobulin-Based Investigation of Spontaneous Resolution of Chlamydia trachomatis Infection". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 215 (11): 1653–1656. doi:10.1093/infdis/jix194. ISSN 1537-6613. PMC5853778. PMID 28444306.

- ^ "Chlamydia Tests". Sexual Conditions Health Middle. WebMD. Retrieved 2012-08-07 .

- ^ Vasilevsky, Sam; Greub, Gilbert; Nardelli-Haefliger, Denise; Baud, David (2014-04-01). "Genital Chlamydia trachomatis: Understanding the Roles of Innate and Adaptive Amnesty in Vaccine Research". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 27 (2): 346–370. doi:10.1128/CMR.00105-13. ISSN 0893-8512. PMC3993100. PMID 24696438.

- ^ Abraham, Sonya; Juele, Helene; Blindside, Peter; Cheeseman, Hannah; Dohn, Rebecca; Cole, Tom (2019-08-01). "Safe and immunogenicity of the chlamydia vaccine candidate CTH522 adjuvanted with CAF01 liposomes or aluminium hydroxide: a first-in-homo, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, stage ane trial". Lancet Infectious Diseases. 19 (x): P1091-1100. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(xix)30279-8. PMID 31416692. S2CID 201019235.

- ^ Follmann, Frank (2020-01-28). "A chlamydia vaccine is on the horizon".

- ^ Christensen, Signe; Halili, Maria A.; Strange, Natalie; Petit, Guillaume A.; Huston, Wilhelmina M.; Martin, Jennifer L.; McMahon, Róisín One thousand. (2019). "Oxidoreductase disulfide bond proteins DsbA and DsbB course an active redox pair in Chlamydia trachomatis, a bacterium with disulfide dependent infection and evolution". PLOS ONE. fourteen (ix): e0222595. Bibcode:2019PLoSO..1422595C. doi:10.1371/periodical.pone.0222595. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC6752827. PMID 31536549.

- ^ Play a trick on, A., Rogers, J. C., Gilbart, J., Morgan, S., Davis, C. H., Knight, S., & Wyrick, P. B. (1990). Muramic acrid is non detectable in Chlamydia psittaci or Chlamydia trachomatis by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Infection and immunity, 58(3), 835–seven.

- ^ Packiam, Mathanraj; Weinrick, Brian; Jacobs, William R.; Maurelli, Anthony T. (2015-09-15). "Structural characterization of muropeptides from Chlamydia trachomatis peptidoglycan by mass spectrometry resolves "chlamydial anomaly"". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 112 (37): 11660–11665. Bibcode:2015PNAS..11211660P. doi:10.1073/pnas.1514026112. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC4577195. PMID 26290580.

- ^ Liechti, One thousand. W.; Kuru, Due east.; Hall, E.; Kalinda, A.; Brun, Y. V.; VanNieuwenhze, K.; Maurelli, A. T. (February 2014). "A new metabolic cell-wall labelling method reveals peptidoglycan in Chlamydia trachomatis". Nature. 506 (7489): 507–510. Bibcode:2014Natur.506..507L. doi:10.1038/nature12892. ISSN 1476-4687. PMC3997218. PMID 24336210.

- ^ "Chlamydial Infections". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library . Retrieved 8 July 2021.

- ^ a b Darougar South, Jones BR, Kinnison JR, Vaughan-Jackson JD, Dunlop EM (1972). "Chlamydial infection. Advances in the diagnostic isolation of Chlamydia, including TRIC agent, from the center, genital tract, and rectum". Br J Vener Dis. 48 (6): 416–twenty. doi:10.1136/sti.48.6.416. PMC1048360. PMID 4651177.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Clarke, Ian (2011). "Evolution of Chlamydia Trachomatis". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1230 (1): E11–8. Bibcode:2011NYASA1230E..11C. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06194.x. PMID 22239534. S2CID 5388815.

- ^ Tang FF, Huang YT, Chang HL, Wong KC (1958). "Further studies on the isolation of the trachoma virus". Acta Virol. 2 (3): 164–seventy. PMID 13594716.

Tang FF, Chang HL, Huang YT, Wang KC (June 1957). "Studies on the etiology of trachoma with special reference to isolation of the virus in chick embryo". Chin Med J. 75 (6): 429–47. PMID 13461224.

Tang FF, Huang YT, Chang HL, Wong KC (1957). "Isolation of trachoma virus in chick embryo". J Hyg Epidemiol Microbiol Immunol. 1 (two): 109–twenty. PMID 13502539. - ^ Clarke, Ian N. (2011). "Evolution of Chlamydia trachomatis". Register of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1230 (1): E11–E18. Bibcode:2011NYASA1230E..11C. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06194.x. PMID 22239534. S2CID 5388815.

- ^ Weir, East.; Haider, Due south.; Telio, D. (2004). "Trachoma: Leading cause of infectious incomprehension". Canadian Medical Association Periodical. 170 (8): 1225. doi:ten.1503/cmaj.1040286. PMC385350. PMID 15078842.

- ^ Somboonna, Naraporn; Mead, Sally; Liu, Jessica; Dean, Deborah (2008). "Discovering and Differentiating New and Emerging Clonal Populations of Chlamydia trachomatiswith a Novel Shotgun Cell Culture Harvest Assay". Emerging Infectious Diseases. fourteen (3): 445–453. doi:10.3201/eid1403.071071. PMC2570839. PMID 18325260.

- ^ Hayes, L. J.; Pickett, M. A.; Conlan, J. Due west.; Ferris, S.; Everson, J. Southward.; Ward, K. E.; Clarke, I. Northward. (1990). "The major outer-membrane proteins of Chlamydia trachomatis serovars a and B: Intra-serovar amino acid changes practice not modify specificities of serovar- and C subspecies-reactive antibody-bounden domains". Journal of General Microbiology. 136 (eight): 1559–1566. doi:10.1099/00221287-136-eight-1559. PMID 1702141.

- ^ Phillips, Samuel; Quigley, Bonnie 50.; Timms, Peter (2019). "Lxx Years of Chlamydia Vaccine Research – Limitations of the Past and Directions for the Futurity". Frontiers in Microbiology. ten: 70. doi:ten.3389/fmicb.2019.00070. ISSN 1664-302X. PMC6365973. PMID 30766521.

Further reading [edit]

- Bellaminutti, Serena; Seracini, Silva; De Seta, Francesco; Gheit, Tarik; Tommasino, Massimo; Comar, Manola (November 2014). "HPV and Chlamydia trachomatis Co-Detection in Young Asymptomatic Women from High Incidence Area for Cervical Cancer". Journal of Medical Virology. 86 (11): 1920–1925. doi:10.1002/jmv.24041. PMID 25132162. S2CID 29787203.

External links [edit]

- Chlamydiae.com

- "Chlamydia trachomatis". NCBI Taxonomy Browser. 813.

- Type strain of Chlamydia trachomatis at BacDive – the Bacterial Diversity Metadatabase

- Chlamydia symptoms with pictures

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chlamydia_trachomatis

Belum ada Komentar untuk "Can a Baby Still Be Born if Mom Has Chlamydia"

Posting Komentar